Image: Author

Our arms are waving our lips are apart;

And if any gaze on our rushing band,

We come between him and the deed of his hand,

We come between him and the hope of his heart.

W. B. Yeats, The Hosting of the Sidhe

* * *

Following on from last years folk horror flavoured adventure on the Slopes of Rathcroghan, I thought I’d take the opportunity of the weekend that’s in it to present you with another. The time: a few years ago. The place: an apparently nondescript rural graveyard somewhere in Middle Ireland. The unwitting (mis)adventurer: yours truly.

* * *

It was the first day of a week of archaeo-field survey and I was supposed to be in the far west of Ireland following in the footsteps of a seventh century bishop, seeking out some of the earliest historically attested Christian sites associated with the cult of St. Patrick. Yet, here I was, walking down a grass rutted country lane, searching for a gate that led toward a half-forgotten graveyard. The location wasn’t even on my official list of sites to visit, but I had been nearby and decided to stop off for a quick poke around. During a previous desktop survey, I had noted several interesting archaeo aspects about the place:

- A late medieval church ruin

- A much earlier medieval looking curvilinear shaped graveyard

- A couple of suspiciously prehistoric looking standing stones in hinterlands

- An abandoned holy well – and most of all –

- A strange looking natural feature on a nearby drumlin that my eyes had been drawn to whilst looking at aerial photography.

Truth be told, it was actually a combination of all the above occurring within a placename containing the Old Irish word túaim; i.e. ‘a mound, bank, knap, tump, or hillock’, but more frequently, in placename terms, ‘a mound, tomb, grave or sepulchre‘ (in the sense of Latin tumulus).

This alone would have made anyone’s archaeological antennae stand up on end. But what really sealed the deal for me was the small matter of there being no record whatsoever of anything resembling a prehistoric mound or tomb in the vicinity.

Coupled with that, somewhere in this particular area, my seventh century bishop had made reference to an early church site. Alas, the full (Hiberno-Latin) placename is now illegible in the only surviving manuscript and as a result has never been identified with any certainty. Later medieval vernacular sources do include an Irish placename for the same area however, also unidentified, yet containing a similar letter or two with that of the first example. More importantly, the Irish placename is qualified by the word Sídh.

(Image: Author)

In onomastic terms this descriptor is generally associated with Sídh Mounds, aka Fairy Mounds. Denuded prehistoric tombs, cairns, mounds or tumuli, often situated on lumps, bumps and hills – many of which were later re-imagined and depicted in Irish myth and folklore as being the underground homes of supernatural beings or fairies known as the Áes Síde.

To have all this whirling around together in one place in an almost perfect archaeological, historical, onomastic storm? To be faced with the prospect of a forgotten prehistoric Tumulus, Síde Mound, or Ferta adjacent an early medieval church site? Perhaps even, the very reason for its initial establishment, reflecting Early Irish Christian agency, engagement and renegotiation with an ancestral past? How could anyone resist?

Long story short, that is how I came to be walking down a lane in the nowhere middle of Middle Ireland. On the off chance of catching a whispered echo of long silenced folk memory. Trespassing across time and space. Waking the dead. Looking for the ghost of a grave in an already ancient graveyard. A ‘túaim’ with a view.

What could possibly go wrong?

(Image: Author)

Reaching the gate, I found myself gazing into a large field with a typical rural Irish graveyard set apart in the middle under a canopy of its own trees. The ground surface within the enclosed cemetery, hunched up like a slumbering hedgehog, bristling with crooked headstones. The tell tale sign of centuries of occupation layers and burials – one on top of one another.

No houses near. No sign of life in neighbouring fields. Not a human soul to be had.

Not wishing to enter without local blessing, I couldn’t help noticing a light track leading from the gate up to a hole in the graveyard wall. People obviously came here. Not regularly, but apparently from time to time. There seemed to be a history of access, without anything to dissuade the casual observer. And so, I took it as an archaeo invitation and slowly entered, making sure to close the gate behind me.

I trudged silently through the field past some of the most chilled out sheep I had ever had occasion to set eyes on. They barely moved out of the way, more than happy to share the landscape with me. Some stared at me with casual disinterest. Most continued to munch away. Windless. Stillness. Bird songless. Nothing but the sound of wet grass being pulled by long dry tongues.

As I approached the graveyard, I realized I was walking over the rushy remains of a medieval fishpond. A soggy bottomed patch of lower ground. Unnoticed. Unrecorded. Ignored even by the resident sheep. The graveyard entrance was a gap in the wall, with only half a gate and one modern looking stone post. The other half was leaning against the outside wall. Recent traces of modern cement and repointing.

Passing through without hindrance, I could see that certain sections of the inside had been recently cleared of overgrowth. Large patches of burnt away vegetation exposing seventeenth and eighteen century headstones. Folkart and figurines stained green with moss. Cracked lichen whites and yellows. The graveyard had been left ‘open for business’ for the sheep to do the rest. Natures own ‘lawnmowers’.

In the centre of the graveyard, the hulking remains of a twelfth century church, half smothered by trees and ivy. Romanesque window. Some decorated capitals. Fragments of moldings and other assorted worked stones scattered on the ground where they had fallen. Squeezed out of their original walls over the centuries. The imperceptible sloth of nature ultimately reclaiming its own.

(Image: Author)

Several sections of the lower walls had obviously been cleared in relatively recent times also, exposing a mishmash of stone phases and construction. The skeleton framework of the church still cradled by gnarled wooden veins and sinewey vines. Their bottom trunks hacked through with saws. Dried out husks of rotting roots. Bone brittle to the touch yet still clinging to the masonry in their death throes. A kind of Twigamortis. The arrested development of delayed decay.

(Image: Author)

I mooched about the ruins for a while. Peering through holes. Parting curtain clumps of long grass. Stumbling over freshly cleared fallen headstones undergoing resurrection from the earth. Long lost monuments of the dead, returning to the world of the living. At least for now.

Eventually, I turned my attention outwards, away from the graveyard, towards the adjacent drumlin ridge that had brought me here in the first place. No matter how much one examines maps and aerial photography, one never really gets a true sense of the elevation of a place until one is standing right in it.

(Image: Author)

The adjacent hill seemed visually higher than ‘on paper’, its crest covered with planted trees since at least the middle of the nineteenth century and partially bisected by a modern boundary fence. Scraggy hawthorn bushes crowding in from the opposite side. Undulating tree roots underfoot.

(Image: Author)

It was the original pattern of plantation in the 19th century around a central curvilinear feature which had peaked my curiosity. Standing there now, in front of it, I couldn’t quite believe what I was looking at. Although obviously landscaped at some point, there nevertheless remained a rather distinctive upside-down saucer-shaped bulge on the summit. Hidden from general view whilst standing below, until halfway up the hill.

(Image: Author)

I walked back and forth, up and down, making sure I wasn’t imagining its shape, still thinking how could something so obvious be hiding in plain sight? Shrouded by trees in the near past, gaps were now starting to show. A dis-articulated tree languished on its side in the pale sun. A hollowed trunk on a hollow hill. Its long dead tentacled roots, once burrowing underground, probably partly responsible for some of its dislocation over the years.

In Rural Ireland, changing agricultural practices and the advent of vehicular transport has limited the way people move around, let alone perceive, the landscape. Large swathes of countryside are rarely visited now by anyone other than their owners. Hedgerows, rabbit paths and shortcuts through fields and over hills, old lines of least resistance commonly used and viewed by locals on foot, are increasingly no more. The price of progress. A loss of local memory. Of local place. Of tombs with a view. No reason to remember or pass it on. No folk, no yolk.

Still, I couldn’t actually be looking at the unrecognized remains of some class of Mound, Cairn, Prehistoric Barrow, or Tumulus, could I? Full of self doubt, I almost laughed it off for a second. Until I realized the amount of large stones lying around the outskirts of the drumlin summit and its immediate environs. Hunks and chunks of stone slabs. Smaller ones, cobbled together in what looked like collapsed field clearance cairns. Larger snag toothed ones, protruding out of the ground in isolation.

Some too heavy to ever shift without supreme effort. Others, perhaps dislodged or recumbant, not far from where they once stood. Monumental, cyclopean rocks, haphazardly scattered, but nevertheless still encircling the outer boundary of the bulging summit. A stone cold whisper of an earlier and outer phase of enclosure.

Kerblike stones. Megalithic monsters. Perhaps once selected, cut or shaped to emphasize something much more important. Dragged up by tremendous communal effort and carefully placed around the mound or summit itself. Outer facing to keep something in. The sacred and the profane.

(Image: Author)

These were not glacial offshoots of bedrock, flaking off an exposed outcrop at the top of an esker. Gravity works downhill not up. Wherever these had come from, they had been brought here at some stage. Left here. Standing sentry across centuries. Whatever else had become of the mound, these had remained, either by design or difficulty in moving. Their lichen speckled flat outer faces varnished even smoother by soft Irish rain and scratching livestock.

(Image: Author)

At one end of the ridge, some effort had apparently been made to marshal some of the megaliths at some stage. Evidence of a linear row placement, aligned on the 19th century tree boundary that had encircled the summit at one stage. A curious little echo of an enclosure in itself, considering that the boundary edge of the whole field was aligned straight through the centre of the mound.

For some reason, its early modern owners had decided to further define the area of the small flattish summit by using the stones already there. A sliver of a slice. Cresent shaped. No practical reason, really, serving only to exclude the very top from the rest of the field. Maybe they had suspected something too.

Growing more excited at the prospect, I started examining the stones in detail on my hands and knees. Running my hands over their smoother surfaces, looking for any indication of human touch. On one slab, facing south east, was a clear indication of a half circular hole, or hollow cup, apparently bored through a thicker surface which subsequently broken off at some stage.

On the opposite side of the same slab, the tapering edge of the stone was seemingly dressed in small round pecked pockmarks. Decorated dimples in the stones surface which ended in a straight line just before the edge. Whatever, or whoever, had caused the marks, had apparently no need to continue the decoration to the end. As if the stone had originally been placed next to another. End to end. An overlapping wedged in edge of a curb.

I scrambled over to another to examine its surface up close and personal. Running my palms over its centre, I thought I felt an undulating rhythm underneath. I leaned back and let my eyes adjust to its stony canvass. There, in front of me, as they settled, I could see the very faint traces of a carving. A thinly spaced triple concentric circle, flowing around and down. Invisible in parts from erosion, slightly oblong, but there nonetheless. A stone echo of an ancient motif that I had seen before in some of the satellite stone age tombs at Loughcrew.

(Image: Author)

I stayed kneeling, in front of it, in silence, my brain swirling with archaeo-thoughts. After a moment, I glanced around, desperate for somebody, anybody, to share my excitement. But of course there was nothing but sheep grazing in an empty field. Windless. Stillness. Bird songless.

For some inexplicable reason, I leaned in and kissed the stone.

***

In the film version of the story, this would be the moment when the camera simultaneously zooms in on my face and pulls background focus out at the same time. The hairs on my neck didn’t just stand up, they practically wilted. My internal organs shivered. My extremities tightened and the skin on my upper back curdled in unadulterated fear. No really.

Nothing to do with the stone. Or my actions. Just the strongest, deepest, insecure feeling of being watched by unknown eyes.

I spinned around, rooted to the spot, in full primitive fight or flight mode, glancing wildly in all directions. Nothing. Nobody. And yet the feeling continued. Every muscle in me screaming silently to run away. But in which direction? Away from what danger?

Taking one last desperate look around, I reached down to grab my camera and backpack and froze. Out of the corner of my eye, at the very bottom of the field behind me, in a overgrown copse of trees, was a figure watching me intently. Still. Grey. Female. In some sort of shroud or veil.

(Image: Author)

At that last moment, before kissing the stone, I had glanced around in this direction, looking for somebody, anybody to be excited with. Presumably, on some unconscious level, my brain or peripheral vision had clocked them. It just took the rest of me a few seconds to catch up.

I’m not going to lie. I nearly shat myself.

I remained frozen. Helpless. Watching her watch me. The ghost of Yeats’ Sídhe Host hanging in dead air. And then, suddenly, back to reality and the realization that maybe this was her field, and that I was the spooky looking one. A strange looking jackeen crawling around on his hands and knees. Kissing stones.

I raised a hand, in greeting. She didn’t move. I took a few steps forward and shouted out ‘Hello there. Are you the landowner? Is this your field?’ And stopped again.

It wasn’t a woman in a veil. It was a man. In a dressing gown. With a beard. Clutching something in his hand.

Bloody hell. I thought to myself. Scared out of his wits. Coming out in his dressing gown in the early morning to check out the suspicious looking bloke trespassing in his field. And then another sudden realization. Farmers have firearms.

Headlines flashed before me. ‘Archaeologist shot dead in tragic misunderstanding’.

I put up both my arms, and took a few gingerly steps forward. ‘Please don’t shoot me…I just wanted to look around the graveyard’. I stopped again. No movement from the farmer. And then, one final, blood draining realization.

He wasn’t holding anything up in his hand.

He didn’t have a hand.

He was in fact holding up what remained of a severed hand.

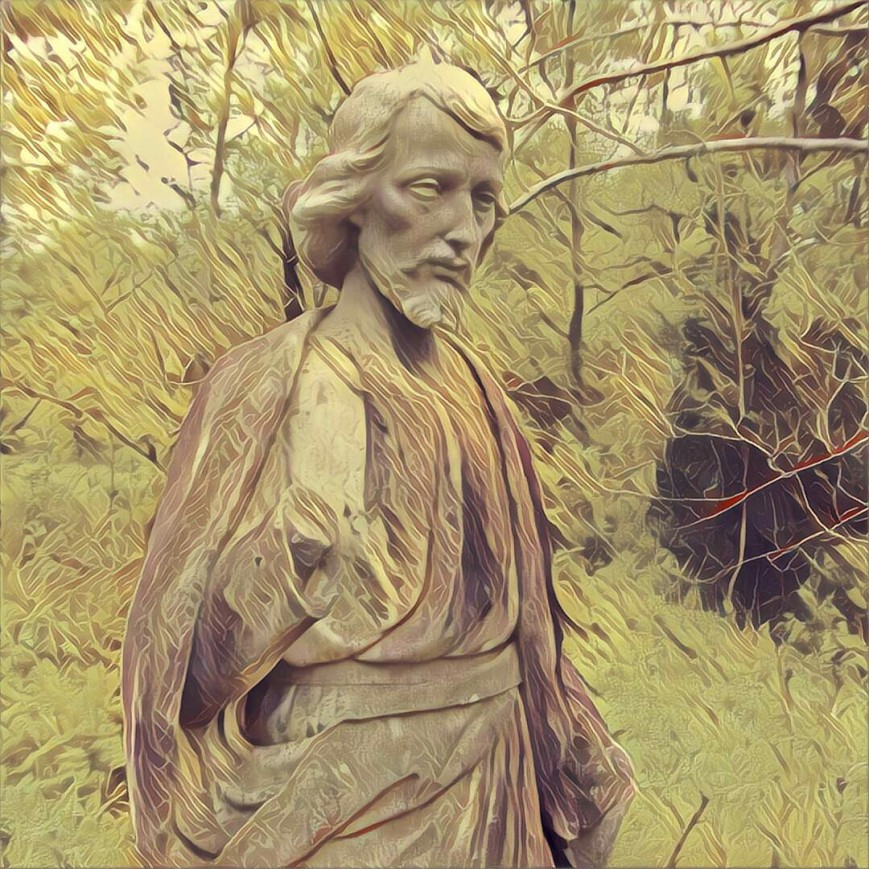

(Image: Author)

It took a horrified moment, but I eventually realized what the hell was going on. I had been calling out, and surrendering to, a life-sized religious statue. A petrified Creeping Jesus. Alone. In the trees. Staring back at me with cold stone eyes. Waving a broken hand. Judging me.

(Image: Author)

In all the previous excitement, I had forgotten about the existence of a Holy Well in the same field. A well that was already half forgotten and mostly unvisited by the time John O’Donovan had first recorded it for the Ordnance Survey in the 1830s. According to the most recent records of the Archaeological Survey of Ireland, there was reportedly no sign of veneration. And so, it hadn’t even been on my radar.

(Image: Author)

Evidently, here it was. An unnamed secret neimed apparently in the process of being restored, alongside the church and graveyard. A recently erected ‘wishing well’ structure surrounding it. Covered with a metal grill. Fresh cement. Presumably a picturesque wooden roof on the way. Maybe even, a bucket.

(Image: Author)

Just beside it, in the rushy overgrowth, were the probable stone remains of the actual previous holy well structure from the nineteenth century. Either that, or a discarded penitential cairn. Slowly sinking into the long grass.

(Image: Author)

And low down, near the feet of Jesus, was perhaps the most terrifying votive offering I have ever seen. A pair of bright shining eyes. Peeping out of a rotting tree trunk. A fecking gnome. His feet fused and cemented into the very tree branch itself. Carrying a lantern which apparently glowed at night, considering there was a solar panel behind his back.

(Image: Author)

Of all the unholy artefacts one could possibly have starting off a ‘new’ old Holy Well with, someone had actually hauled a second hand, discarded, broken, life sized religious statue and a solar powered LED Garden Gnome, all the way down here – and then cemented them both in for good measure.

What fresh hell had I stumbled into? What on earth could be coming next? And what if I was still there, when they came?

I snapped a few hurried pictures, paid my respects and left sharpish. On the off chance that someone else, someone real, may in fact have been watching me. Someone who really liked recycling Garden Gnomes. Jesus statues. Maybe even, wandering archaeologists.

Skedaddling back to the drumlin, I took a few more quick photos of the rock art, and made a mental note to come back another time for better pictures. Of course, that would involve returning with a better camera and a powerful torch.

At dusk or twilight.

To a suspected prehistoric mound on a hollow hill.

Beside a disneyfied druidical gnomic grove.

In a feral field in Ireland.

——————————

(Image: Author)

—————————–

Notes:

*All images are my own, enhanced via Prisma for stylistic effect.

*A local project of conservation/cleaning work in the church and graveyard was apparently undertaken in the 1990s, and once again, around about the time of my visit a few years ago. At the same time, the holy well was re-dedicated and a local group was involved in periodically renovating it. While I have obviously played up certain aspects for comedic and over-dramatic purposes, I wish to cast no aspersions on those involved. Community interest, activity and involvement in local heritage/archaeological sites is a venerable endeavour to be lauded, commended and encouraged. And I am first in line to do so.

*Regarding the previously mentioned indications of potential prehistoric carvings/motifs on some of the stones, see the following photos:

(Image: Author) One of the more substantial ‘kerbstones’ lying around. Note the semi circular ‘bore-hole’ on the left edge. On the right, faint traces of ‘pecking’

(Image: Author) Close up detail of right hand side, as above. Note ‘pecking’ and ‘pockmarks’ ending with a distinct linear boundary at extreme edge.

(Image: Author) Photo enhanced close up detail of concentric circle motif

(image: Author. Photo enhanced close up detail of concentric circle motif)

What a brilliant story! It has everything, archeology, history, scary bits, hilarious bits, very exciting bits… I love it! The photos are great too!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cheers. Very kind.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful story!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Loved it. Thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Maybe you must leave archaelogy and try some substantial neo-gothic writing… 😉 well, or neo-romanesque. Very nice the Prisma of whatever app. Love it!

LikeLiked by 1 person

class story! Well done, and the pictures/photos are really great alongside the story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“A fecking gnome!”. I think that needs to be on a t-shirt.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: A Thig Ná Tit Orm: The Last Picture Show | vox hiberionacum