One of the first things you noticed about Charlie Doherty was that everyone had, or wanted to have, a word with him. He appeared to know almost everyone at conferences. He’d slip quietly into rooms and theatres during presentations, trying to be inconspicuous, and then spend the next few minutes nodding and acknowledging furtive salutes from half the audience. I remember attending a lecture from a visiting scholar once. Charlie arrived in and took a seat at the back. After it finished, there were more people looking to talk to Charlie than the visiting scholar.

One of the other things you noticed was how fast he walked. For such a relatively small man, he could move like the clappers. ‘I have to be somewhere, walk with me,’ he’d say after a lecture, and a clatter of undergrads would then follow him around a maze of corridors in UCD, he answering questions on the fly and giving pointers to further reading. I realized early on that he probably did this from experience because it was the only way he would ever get away from the end of a class without a thousand queries. Oftentimes, I struggled to keep up with him. A man over twice my age. Chasing him around, he introduced me to lesser-travelled campus shortcuts I never knew existed.

We had all heard of Charlie before we met him. He was regularly cited in other people’s lectures and assigned readings. “Early Medieval Ireland?” people would say, “Have you had Charlie, yet?” Following my introductory baptism of patrician fire, I knew that for the next few years, I would be taking every early medieval module that was possible. Back then, Early Irish History as a dedicated subject was being phased out, if it hadn’t already gone. However, with judicious selection of the modules on offer between Charlie Doherty and Elva Johnston, one could essentially get an Early Irish History degree at the expense of also having to take a few boring compulsory modern history classes in addition. That’s what some of us did, anyway.

The first class we actually had with him wasn’t part of the History course but rather Celtic Civ. He, along with others, was a guest lecturer and gave an introduction to Early Irish literature. Sitting quietly at the top of the class, glasses perched on his nose, he welcomed us with a soft Derry accent, twinkling eyes, and a gentle smile. Within 5 minutes, I was addicted to his enthusiasm. When he found out that not all of the class were American JYAs chasing Clannad, and that a few of us were archaeology students too – who were also taking early medieval modules – he started to tailor the classes to fit us. By the time we came to his own medieval classes proper, he’d already given us a solid grounding in advance.

Charlie’s regular module handbooks were collector’s items. Unlike everyone else’s plain black and white A4 sheets, Charlie’s were in landscape, with bright colours and text over transparent fading background images from medieval manuscripts. He delighted in full-screen illuminated PowerPoints, playing around with and admiring different fades and dissolves between slides. He was interested in the potential of new technologies, regularly enquiring about the latest archaeo tech coming down the line. He was very impressed with one of his former students who went on to work in computer games. The student had sent him a 3D model mock-up of St. Brigit’s Basilica in Kildare as textually depicted by Cogitosis. “Isn’t that fantastic?”, he’d say. “You never know where Early Irish History is going to bring you.”

Patrick. Brigit. Columba. Early Irish Hagiography. Hagiographers. Armagh. Rome. The Cult of Relics. The Cult of the Saints. Early Irish Church in context. Peregrinatio. Pilgrimage. Proto-monastic towns. Ecclesiastical Familia and their Machinations. The Book of Armagh. The Liber Angili. Vikings. High Kings. Bishoprics. Dynasties. Territories. Annals. Charlie literally introduced me to everything Early Medieval Irish. More importantly, he showed us how to approach and interrogate the material with eyes wide open to political and economic contexts. Excavating texts so as to read between the lines.

His introduction to Múirchú’s Vita as a corporate commission by Áed of Sléibte was incredible, tying Patrician hagiography together with the Additamenta, Cáin Adomnán guarantors, Annals, and Leinster ecclesiastical power dynamics. My brain melted with the scale of interconnectivity if you had a wide range of exposure to Early Medieval sources in context. A few minutes later, he had moved on to how Múirchú’s opening included a playful textual pun on his own name. These people came alive, along with all their motivations, biases, and predilections. On several occasions, he’d even surprise himself. He’d suddenly stop in mid-flow and take off his glasses, wiping them and staring at us. “You know, I’ve never made that connection before. I must write that down.”

I will never forget an afternoon in October of second year. We had moved on to Tírechán. Charlie was pointing out just how dense the text was despite surface appearances. Full of names, places, and landscapes to unpack. He paused, again mid-flow, took off his glasses, and looked directly at me. “Of course, nobody has really done any work on this. ‘Someone’ should.” Right then and there, before I even knew that I would go on to need them, or even realized that I was looking for them – he presented me with MA and PhD topics.

On another occasion, at the end of second year, he paused again, took off his glasses, and looked wistfully out the window. “Do you know what’s incredible? We have all the sources we are ever going to have from Early Medieval Ireland. The last one came to light about 200 years ago. We’re never going to find any more. We just have to make do with what’s come down to us.” A few weeks later, I opened a newspaper to see the startling announcement of the discovery of the Fadden More Psalter in an Irish bog. On our first class back with him in September, we awaited his arrival, grinning widely. He walked in, put down his bag, and took off his glasses. “Well,” he said. “I’ve never been so glad to be so wrong.”

Somewhere near the beginning of third year, I missed the only class of his I ever would in over two years. I heard afterwards from my classmates that Charlie had walked in, put down his bag as usual, and looked around. “Where’s Vox? It’s not like him to miss a class. Is everything all right?” Henceforth, they referred to me as ‘Charlie’s Boy’ in time-honoured Irish slagging fashion. I laughed it off but was secretly delighted.

By the end of third year, through attrition and other specializations, there were just five of us left in his class. On a beautiful warm May morning, we dutifully herded ourselves along with hundreds of other students into the RDS stadium for our final examinations. Back then, we were required to write longhand essays in three hours from a selection of questions on the final paper. Being just five students in an obscure specialist module, we were naturally shunted around from one section to another, and eventually placed, last minute, in a godforsaken corner of the arena, where we received our scripts. The exam started at 9 am. All heads down. Forty-five minutes later, I heard soft footfall from behind. Presuming it was an invigilator, I paid no heed. A voice in my ear, a soft Derry accent, enquired, “Is everything okay with the paper?” I looked up at Charlie and gave him two thumbs up for the two Patrician questions. He smiled and checked with all the other students before heading off. He had spent the last 45 minutes walking up and down all the rows of desks in the RDS until he found us. Five students. There were lecturers who had 50 people in their classes who didn’t do that.

The following year, I found myself back in his office. He had promised me for ages that he would give me an academic recommendation for an application. Being eternally busy and popular, he never quite got around to it. I nabbed him one day passing the photocopiers. “Charlie, the deadline is today.” “Oh right,” he said, “Walk with me.” We sat in his office for the last time and he started typing out a reference. Twenty minutes later he was still typing, stopping every now and then, to look wistfully at me, before going back to the keyboard. When he was finished, he printed it from his little portable printer, folded it in three, put it into an envelope, and very pointedly sealed it. “There you go, all the best”, he said with a knowing smile. I had to submit it as is. To this day I have no idea what he wrote. I got the application.

Fast forward several more years, and I was presenting at a conference. Always outwardly confident, I was shitting myself inside. For some reason, several heavy early medieval hitters had shown up, despite there being far more important and interesting parallel sessions elsewhere. A few minutes into my spiel, Charlie slipped quietly into the room, trying to be inconspicuous, but spent the next few minutes nodding and acknowledging furtive salutes from half the audience. I knew then that everything would be all right. It gave me an opportunity to do something I had long wanted to do. Citing him for an obscure identification he had made years before based on an even more obscure text and showing him why it worked on satellite imagery too. For just a brief moment, we swapped roles, and I got to tell him something new.

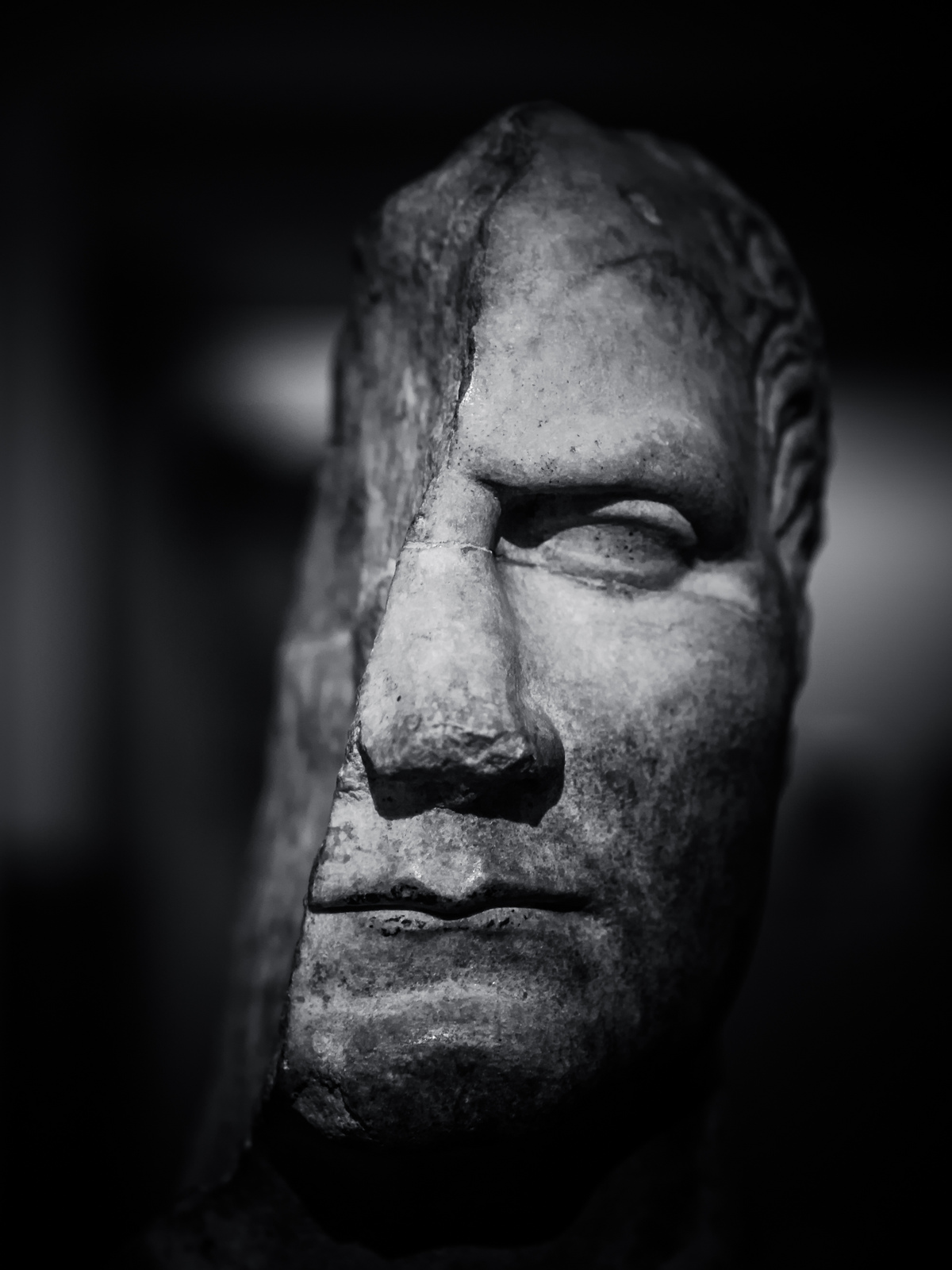

I saw him less and less after that. I’d run into him very occasionally at his local supermarket near my parents’ home. Always thought it was funny to discuss early medieval tidbits in front of the spuds. A few years ago, I found myself, quite by accident, passing Sléibte/Sleaty, Co Laois. I stopped at the church for a poke around and thought back to that very day with Charlie and Áed when I had nearly ‘suffocated by imperfect deglutition of aliment‘. Brigit begat Patrick. Tírechán begat Múirchú. FJ Byrne begat Charlie. I took a picture to prove I had eventually made it there after all this time. It’s the title picture of this post.

***

I was greatly saddened to find out that Charlie Doherty passed away recently. My deepest sympathies to all his family, friends, and colleagues. We genuinely will not see his like again. I wish I had far better words to express how much of an influence he was on me, on my research interests, on my learning and development. He is largely responsible for anything and everything early medieval I have ever attempted. Including starting this blog way back in the day. It’s nothing compared to the decades of students he taught who thought the world of him. I’m just one of many.

Requiescat in pace.

I have always been, and always will be, Charlie’s Boy.