I have taken my little talent – a boy’s paddle-boat, as it were – out on this deep and perilous sea of sacred narrative, where waves boldly swell to towering heights among rocky reefs in unknown waters, (a sea) on which so far no boat has ventured…

There’s something deliciously ‘early medieval’ about rowing wooden boats. No matter how much modern gear you happen to pack inside, there’s nothing ‘modern’ about the act of rowing itself. Of propelling a craft through the water by sheer power of human strength alone. Of pushing backwards from your legs a sweeping oar and seeing it catch and glide through the water, feeling a little surge forward in tandem with the others. Of riding into and cresting waves on the open sea. Of slinking through flat rivers. Of sitting in the bow, bobbing up and down, face forward to the horizon with hands on each side, feeling the wood hum and vibrate.

Wooden boats are most alive when they are moving. No really. You can hear them breathing, whalelike, an excited gurgling sound underneath, like a cistern, as water bubbles flow down the hull in transit. You can literally feel its synchronized heartbeat between the reach and return of the oars twisting and sliding between two thole pins – hard and soft wooden arteries – producing a dull ‘thud-dum’, ‘thud-dum’, ‘thud-dum’. A leathery wooden pulse pumping through the boat. The work of human hands.

It can, at times, get strangely hypnotic. Especially when on the board chatter had died down and people have settled into a good rhythm. The cox has little need to correct or instruct and the only thing left – is the open sea, the repetitive wooden heartbeat and ones own thoughts. My archaeo-imagination being what it is, I am usually transported back in time, to early medieval Ireland – not that hard when one is traversing the eastern Irish coastline in a clinker built craft, passing entire counties and landmarks once viewed in the same manner by seafarers from the north and still enshrined – despite anglicization – with Old Norse placenames.

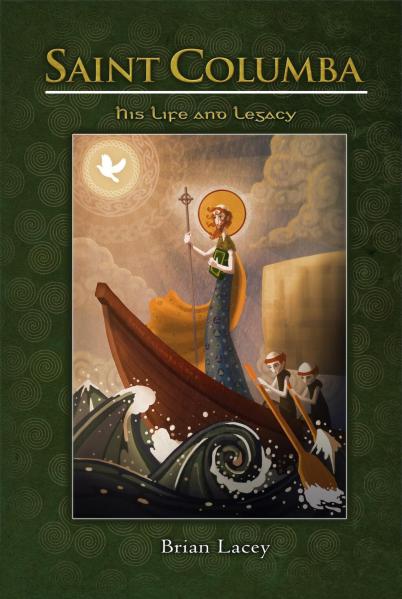

Or perhaps, even further back, to Sixth and Seventh Century Ireland, when little boats and big seas occupied Early Christian literary imaginations as well as daily realities. Immrama. Navigatio. Peregrinatio. Exiles for God, adrift in the sea, seeking a retreat from the world. Romantic figures like Columba. Adómnan. Brendan. Island hermitages like Iona. Lindisfarne. Inishbofin.