Image: Emmet Ó hInnéirghe (Used with Permission)

Introduction

It’s Thursday. It’s March 17th. If you’re a regular, you know what that means. To celebrate the day that’s in it and in keeping with time-honoured blog tradition, I hereby present my annual Patrician-themed rambling extravaganza – a forensic examination of a lesser spotted feature within the writings of the historical Patrick himself. This year, I thought I’d take a look at what appears to be a fleeting throwaway line from the Confessio concerning Patrick’s escape from captivity and subsequent two hundred mile journey across Ireland to an unknown port.

I have actually touched on it before, ever so slightly. Previously, I wrote a short audio book for Abarta Heritage on Patrick’s six years in captivity; and towards the end of the section dealing with the young Patrick’s decision to make a break for freedom, I concluded with the following line:

If there was one thing that Patrick would have known after six years under Irish skies – it was the direction home. Towards the rising sun.

Aside the fact that it reads like an over-dramatic hollywood-esque voice-over (it sounds much better in the book, honestly!), its both over-exaggerated and simplified. For one thing, the sun doesn’t rise or set directly east/west, except for the equinoxes. In Patrick’s time as a slave in western Ireland on the shores of Killala Bay, it actually would have risen North East over the sea from his perspective during the summer months. Nevertheless, it was my little way of acknowledging a single line in the text of the Confessio and suggesting that there may be more than meets the eye to it.

The particular line centres on the youthful Patrick’s decision to leave his captor and head 200 miles across Ireland to a waiting ship/port – without knowing anybody or where he was going. Why is it important and worthy of examination? Well, I would suggest that it carries several implications. Celestial symbolism and biblical frameworks aside, Patrick did escape from captivity and he must have crossed Ireland somehow and I think a closer look hints at just how he may have done so. In addition, it opens up several other aspects:

a) its a further inference (other than his own words) to his youthful captivity being on the western Irish coast – something which continues to be questioned by certain sectors, despite modern Patrician scholarship being widely agreed on the matter

b) it forms a crucial event horizon (quite literally) in Patrick’s later theological framework and motivation for his mission

c) it potentially offers an indication of how he may have come to be there in the first place – as in, the manner in which he was transported to Ireland from Western Roman Britain.

And I Would Walk Two Hundred Miles…

Here’s the line in question, within its expanded passage context:

Et iterum post paululum tempus audiui responsum dicentem mihi. Ecce nauis tua parata est. Et non erat prope sed forte habebat ducenta milia passus, et ibi numquam fueram nec ibi notum quemquam de hominibus habebam. Et deinde postmodum conuersus sum in fugam et intermisi hominem cum quo fueram sex annis et ueni in uirtute Dei qui uiam mean ad bonum dirgebat et nihil metuebam donec perueni ad nauem illam…

‘And again, after a very little time I heard the answer saying to me, ‘Look, your ship is ready’. And it was not near, but perhaps two hundred miles [lit. ‘it had two hundred thousand double paces], and I had never been there, nor did I have any single acquaintance among men there, and then later I turned to flight, and I abandoned the man with whom I had been for six years, and I came in the power of God, who was directing my way towards good, and I was fearing nothing until I came through to that ship…’

Confessio 17 (Translation: Howlett, 1994, 62-63)

In short, it does exactly what it says on the tin. Patrick imagines/dreams of a (divine) voice telling him it is time to escape, that there is somehow a ship at a great distance and that he should go. He does so, despite not having any knowledge of where he is going, trusts to what he interprets as divine guidance and direction along the way, and leaves his captor of six years. So far so good.

Devil in the Detail

But take another look at the one detail provided – the stated ‘two hundred miles’. In a text famously lacking in incidental detail, one should always take note of when Patrick actually includes incidental detail, because he always has a good reason for doing so. How could he have known the approximate distance beforehand, especially when he makes the point of his never having been there? Obviously, he couldn’t have at that time. What we are reading, of course, is his account of events written down decades later and the specified distance is presumably knowledge gained afterwards.

How could he have come to that figure? I can think of only two ways. Either asking someone who had done so, or having done it himself in a manner involving a keen observational interest in keeping track of time and distance. More on this shortly.

Who gains from such information? Is it an integral part to the story of his escape? Not really. As far as his contemporary audience was concerned – he crossed Ireland. End of story. The main point of the episode is the presumably hard and difficult journey, on his own, under divine guidance. How far he traveled doesn’t actually add anything further other than a nice rounded measurement. Indeed, on the question of his audience, who would even appreciate or recognize such detail?

Size Matters

In both his documents, the Confessio and Epistle, Patrick was addressing multiple audiences and networks – his supporters and detractors in several scattered communities of Christians in various parts of Britain and Ireland. Who in Fifth Century Britain would know if that figure was realistic or not? Who in Britain would even care? It seems to me, that the detail supplied could only have been appreciated by those in Ireland who had a rough knowledge of the approximate size of the island from west to east (via time/distance traveled). By the same token, including such a specific detail of measurement to an Irish based audience already familiar with such a concept would have been a risky venture, if it wasn’t based on some underlying truth. In other words, if he had been lying or exaggerating the actual distance, it would have been abundantly clear to an Irish audience (‘How big? Ah Jaysis, Patrick, you’re talking shite now!’).

As such, the specified distance of two hundred miles makes no literary or narrative sense unless it was underpinned by fifth century geographical reality, and even if so, could only have been appreciated by those familiar with the extent of Ireland’s interior. Patrick’s deliberate referencing of the same in the Confessio seems to be an attempt to emphasize his own local knowledge of two extreme locations: the scene of his captivity, the scene of his escape and the distance between them. Set amidst the background of the Confessio’s overall defense of his mission (against detractors who were accusing Patrick of having ulterior motives), this forms an important part of Patrick’s stated explanation – that his whole life, from enslavement, escape from captivity and return as missionary was brought about under divine providence.

Not only that, it suggests that his later missionary field (i.e Confessio 51) included some of the same geography, or more specifically, the general area of his captivity (The famous ‘Wood of Foclut’, as suggested by his own words at the end of Confessio 23). Why tell an Irish audience where he had been captive and where he had escaped from, and why say where he had eventually returned, (incidentally providing his credentials in terms of recognizable distance) if it wasn’t true? Or more specifically, why give such detail if there wasn’t a way for some of them to ascertain it for themselves?

All in all, Patrick’s seemingly fleeting and incidental references on the subject make a lot more sense – and carry a lot more weight – when viewed in such terms by such an audience. They are his version of textual ‘Easter Eggs’; insider knowledge, only of interest to, and only recognizable by, some of his Irish audience. An audience to which he was directly appealing as a result of criticism from British Christians who, ironically, would not have even realized their significance despite receiving them in the same communication. Fifth century Patrician sub-tweeting, at its very best.

And I Would Walk Two Hundred More

Turning back to the reference again, what exactly did Patrick mean by ‘two hundred miles’? His actual words ‘ducenta milia passus‘, as stated in translation, literally mean: ‘two hundred thousand (double) paces’. Unsurprisingly, this illustrates that Patrick’s conception of distance was informed by the imperial Roman system. (One pace being 5 Roman feet, Imperial Roman mile being 5,000 Roman feet, or close variants thereof, depending on time and province). Naturally, over the years, many scholars have sought to use this measurement (with compass in hand) in order to attempt to pinpoint a range of locations. While I am reluctant to repeat such experiments, I do think that a brief exploration is useful, if nothing else than to provide a rough idea of what he was actually talking about. If anything, it serves to hammer another historical nail in the coffin of a ‘Slemish location’ by underlining the fact that his starting out point (scene of his captivity) needs to have been situated at the western extremities of Ireland. After all, there isn’t many other locations from where one can travel such distance ‘across’ Ireland.

Oh Sweet Jaysis, Maths?

Breaking it all down, gives us the following:

- One (double) pace = c.5ft.

- 200,000 double paces = 1,000,000ft = 304.8 Km or 189.3939 modern miles.

Now, always conscious and not a little suspicious of historical uniformity, lets take Patrick at his own words and focus on ‘double paces’. I’m a pretty average size and height for a male (5ft 10) and as any half decent archaeologist will be able to tell you, my standard walking pace is 0.76m or 2.49ft. (Good for surveying in the field – convert from paces later!) My double pace would therefore be 1.52m. Multiplied by 200,000 gives 304 Km or 188 miles.

Not bad. Not bad at all. Its pretty realistic, then, as now.

Now, lets bear in mind that such travel would obviously not be in a straight line over even terrain, and factor in a margin of error, both sides, i.e. a little more and a little less, depending on obstacles etc. Say, 30 miles for arguments sake.

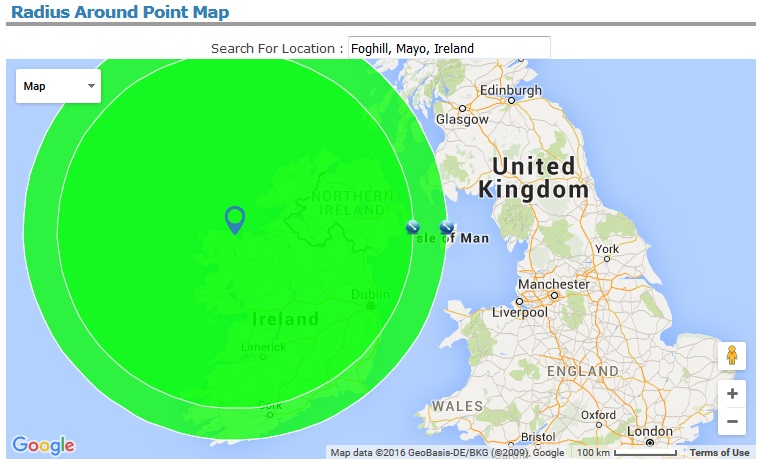

Screengrab: freemaptools.com

Stay On Target, Luke

Above is what a radius of 188 modern miles from modern day Foghill, Co. Mayo (Close approximate of the original Wood of Foclut) looks like – in conjunction with the lesser radius of 158 modern miles. (I left out the third radius of 218 miles as its encompasses only sea & land beyond Ireland). The outer one, the 188 miles, barely intersects the islands landmass, giving us only two possible locations – the extreme tip of South East Wexford and deepest darkest Southern Cork. However the second one, attempting to approximate a certain amount of ‘over-traveling’, gives us a somewhat clearer idea. It demonstrates, hopefully, the inherent realism in Patrick’s stated distances as well as opening up the south east and southern coasts as potential areas in which he eventually found passage. Such a zone would certainly match his depiction of both a busy port, frequented by maritime traders and (probable) British or Gaulish crews, some of whom eventually took him on board.

Of course, the big question now is, why would a Runaway Patrick have crossed Ireland ‘the long way’ as opposed to heading towards the closer north and north eastern coastlines? For that, we need to return to his own words and my own over-dramatic opening quote:

And it was not near, but perhaps two hundred miles and I had never been there, nor did I have any single acquaintance among men there, and then later I turned to flight, and I abandoned the man with whom I had been for six years, and I came in the power of God, who was directing my way towards good…

“If there was one thing that Patrick would have known after six years under Irish skies – it was the direction home. Towards the rising sun”.

Going Home, The Long Way Around

Well, if there was thing that Patrick would have known after six years herding livestock under Irish skies in modern day north county Mayo, its that the sun didn’t rise in the east during the summer time. It actually rose in the North East, which to him, would have appeared over the sea. Following it, even attempting to make corrections, would not have been an easy option.

He wouldn’t have known exactly where he was, but he would surely have gathered that it was the extreme west. He probably could have put two and two together in any case, either by his initial journey there or by talking to others, Irish or British people (elsewhere he mentions the maintenance of a British identity among second generation slaves born to captives) and come up with a notional direction. Towards the Irish coast most likely to contain trading ports and emporia.

Why the summer? Obviously, the optimum season for escape – longer days, better weather, fairer maritime/trading conditions, the likelihood of shipping traffic – coupled with after the start of May, when herds were likely brought to upland pastures and before the end of summer, around August, when harvests were being recovered.

That He Might Face The Setting Sun

In his own words, he had apparently only ever been with one captor, in that one general location having no experience of the rest of Ireland. So his escape and journey really was an act of faith in what he perceived as divine direction – but perhaps underpinned by his own observation. One which was possibly, metaphorically and literally, provided by the sun. Not the rising one. That of the setting sun.

Turning your back to captivity, to enslavement, to the very setting sun itself, from North Country Mayo in Western Ireland during the fifth century would have provided a very simple direction to follow – South East. Running away into the unknown taking his bearings every evening, even if cloudy, would have brought him, eventually, to the South Eastern coastal extremities. Using a nifty web app, The Photographer’s Ephemeris (TPE) (available to download in a variety of operating systems) here’s how it would have worked:

Ephemeral Ephemeris

Above is a visualization of sun and moon rise/set, projected over google maps, for May 1st, 431 AD. I picked one of the traditional irish annal dates for Patrick, only as an example. Truth be told, the angles and azimuths have barely changed in the succeeding centuries and it doesn’t make much difference at all – but in the interests of accuracy, I have dated it to early fifth century. (Personally, I reckon it was late fourth century AD).

Note the NW sunset and NE sunrise. Clicking through and doing it yourself, day by day, will give a real indication of just how much everything (except the sunrise/set) actually fluctuates as the season progresses. Now note the projected grey line. This is the opposite direction to sunset, literally 180 degrees to the given angle. For what follows, keep an eye on the grey lines in these ‘snapshots’ of angle and direction throughout the summer months, from Early May to Mid July…

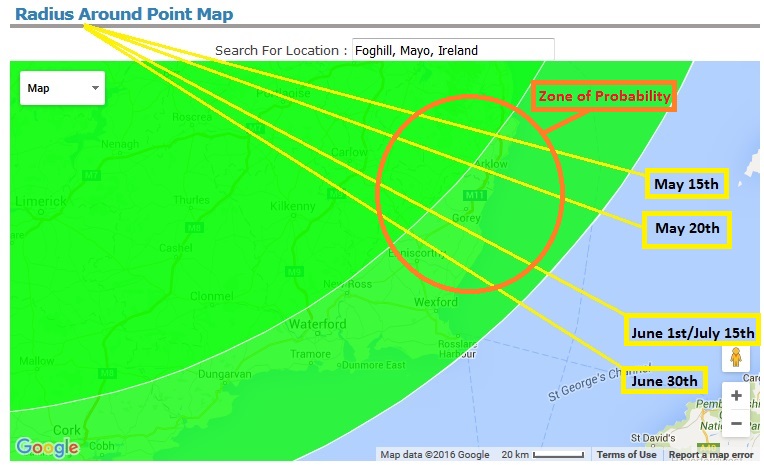

In terms of the seasonal range, such a spread of ‘pathways from the setting sun’ gives us an interesting array of ‘exit points’ in the south east. See for yourselves in these close ups:

Essentially, between May and the end of June, after having been drifting to the south, the projected angles/pathways start to turn north again. All in all, this gives us a fairly limited range of coastal areas. In the interests of clarity, and with no expense spared, see the all-out effort I went to in order to illustrate same in paintshop:

Whats the Feckin’ Point?

So, we have a range of sites extending from Wicklow town in the north, through modern day Arklow, Gorey and almost to Wexford city itself, before it turns back on itself and starts heading towards the north again. There’s a reason they mostly have anglicized Viking names, of course. These sites and locations, natural harbours and estuaries, likely early medieval ports themselves, were very much favoured by the Norse when they established settlements from the ninth century onward.

So what, Vox, I hear you say. Whats the big deal? Well, it wouldn’t really be a big deal, except… we happen to have some interesting tidbits from later hagiography specifically concerning the triumphal return of the Saintly Patrick, now a super saintly caricature of course, off the east coast of Ireland. Despite having them run more or less straight to Ulster, or the royal plains of Brega in Co. Meath in order to conduct symbolic/metaphorical ‘grand arrivals’ – each inserts a strange little foreshadowing event. For example, in Muirchú’s Life of Patrick, the saint is depicted as having first landed in the general vicinity of Wicklow/Arklow first.

…quasi in oportunum portum in regiones Coolennorum, in portum apud nos clarum qui uocatur hostium Dee dilata est…

…reached a convenient port in the district of Cúalu (Wicklow) a well-known harbour of ours called Inber Dee…

Strangely, he does this before he has done anything else, apparently immediately wishing to ‘redeem himself’ from slavery. In a way, its almost as if Muirchú was making a conscious association with his physical return and his earlier escape. Following on from this, in the later Betha Phatraic, we get a vernacular version based on Muirchú but with added flourishes…

O dha-ruacht Patraic co h-Inber n-Dea h-i crích Laigen & co aroile fích comfocus ní fuair failte inntib. & mallachais Patraic an inber-sin conid etoirthech o sin ille h-e. & co tanic muir darsin tír-sin. Nathíi mac Garrchon tra is e ro diult fri Patraic.

When Patrick came to Inver Dea in the territory of Leinster, and to a certain hamlet hard by, he found no welcome in them, and Patrick cursed that rivermouth, wherefore it is barren (of fish) from that to this, and the sea hath come over that land. Nathí, son of Garrchu, was he who denied Patrick.

Even Tírechán, who depicts Patrick as arriving in a ‘Party Boat with a Plethora of Gaulish Hangers On’ off the east coast, has Patrick’s very first act as stopping off on Inis Pádraig (“St Patrick’s Island”) located just off modern day Skerries. More interestingly, the depicted location of Inber Dee/Hostium Dee also plays a role in later Palladian episodes in early Irish Literature – himself later associated with Leinster in general and some particular sites in Co. Wicklow – not to mention the long held scholarly opinion that certain elements or features of Palladius and Patrick were possibly conflated in the early medieval period.

Inber Dee

i. deenavis dilata est in regiones Coolennorum in portum apud nos clarum qui vocatur Hostium Dee, A. 2 b; ¶ I. nDee i crích Cualand, I. 147 b, Ll. 159, Bd. 8, Lis. 4 a (Ll., Bd. and Lis. have I. nDe); ¶ Dea mac Dedhadh, a quô I. nDea a Crích Chualand, Sa. 27 a; ¶ Cell Dara do orgain do Gentin ó I. Deaae, Ui.; ¶ ó I. Deaa, Mi.; ¶ at Arklow; ¶ I. Deae i Crích Laigen, Lb. 26 a, Tl. 30, 32, 34, where Nathi Mac Garrchon opposed Patrick and Palladius; ¶ I. Deaghaidh, K. 156 a; ¶ I. Dedhaigh i Crích Cualann, Bb. 198 b; ¶ I. nDee, i.e., the mouth or estuary of the r. Dee is where it enters the sea immediately below Arklow; ¶ the r. Dee rises about Glenn Da Locha, the earlier name of which was Glenn De, and flows on to Arklow; ¶ Vallis Duorum Stagnorum quae quondam Scotice vocabatur Glean(n) Dé nunc autem Glendaloch in regione quae dicitur Fortuatha (Vita Caemgeni which Ussher quotes, Up. 956, and a Vita which belonged to Wardaeus O.S.F., quoted in Bk. xx. 310, 313); ¶ the Glen was named fr. the r., as in Glenswilly, &c.; ¶ now, the Avonmore (Abhand Mór, al. Great River), is formed by a confluence of rivulets in the vicinity of Glendaloch, is joined by the Avonbeg (or Little River) at “The Meeting of the Waters” below Rathdrum, is joined by the Aughrim at “The Second Meeting of the Waters” at Wooden Bridge, and thence, as the Avoca, a superbly scenic r. for 4 m., under the name of Avoca, enters the sea at Arklow, al. Inber nDee; ¶ v. Avonmore and Ovoca, Pgi.; ¶ this is further confirmed by I. nDee being connected with Ui Garrchon and Ui Dedad, which point to Arklow—see those words; ¶ O’D. says, Fm. i. 130, fr. the situation of Cualann and Ui Garchon, in which it was, it is more than prob. that it was Bray; ¶ the mouth of the Vartry r. at Wickl. Harbour, Mi., Cri., Ct., Mm. 485; ¶ so say the Bollandists, Colgan, O’Don., Hen., O’Curry, Todd, Bury. i. ndelbinne; ¶ Ls. i. 76; ¶ v. I. n-Ailbine.

Onomasticon Goedelicum locorum et tribuum Hiberniae et Scotiae

Image: Emmet Ó hInnéirghe (Used with Permission)

You’ll Never Walk Alone

I don’t know about you, but I think its extremely interesting that various depictions of St. Patrick/Palladius within early medieval hagiography, despite being written over two centuries later or more, include very specific associations with the east coast – with modern day Co. Wicklow in particular. It raises the possibility that perhaps they were aware of, or had reason to include the area as having some residual association with a pre-existing Patrician tradition or folk memory.

Even if this wasn’t the case, it seems to me that early medieval audiences, in reading Patrick’s own words and measurements, seem to have had no problem with focusing in on this part of the country for his arrival by sea – despite an emerging Armagh narrative framework which favoured the portrayal of Ulster locations. All in all, when yoked together with Patrick’s own words, and the prospective ‘sunset model’ contained above, it all seems to come together – in admittedly various disparate guises – towards a specific endpoint, or starting point, whichever takes ones fancy.

As to what the two hundred mile journey represents to the historical Patrick’s theology and his original transportation to western ireland…that, as they say, would be an ecumenical matter.

To Be Continued…

*********************************************************************

With grateful thanks and much appreciation to Derek Ryan for some technical discussions and also Emmet Ó hInnéirghe for the great images, used with permission.

Fascinating article. Patrick’s journey across Ireland, as an escaped slave in the early 5th Century, sounds almost impossible, yet he wouldn’t have mentioned it if there were people who could disprove it.

I’m not a historian, but I have some experience of Bushcraft and survival, so the story seems even more incredible to my ears. The journey may have taken months, and while water wouldn’t be difficult to find, I can’t help wondering what he ate. There is precious little in the way of wild food until the Autumn months, and hunting and fishing are unreliable. Add to that the need for him to remain undetected on his journey, avoiding major routes of travel, such as rivers, and it becomes even more incredible.

I suspect Patrick had help on his journey. Perhaps other Romano-British slaves in Ireland, willing to help a runaway slave with food, a place to sleep, and warnings about which routes to avoid. Perhaps they were even some Christian communities. Whoever it was, it just doesn’t seem likely he could have traversed Ireland, hunted and fished for himself, and never have been identified as a runaway slave.

Maybe that’s why he goes out of his way to mention his journey? Maybe there were communities in Ireland that had a tradition of having helped the young missionary when he was escaping?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cheers, Liam. Interesting point about the bushcraft, which is a fascinating prospect, especially as you say, at that time of year. There was a famous argument once, amongst older scholars, of a kind of Christian ‘escape network’, along the lines you mention. Although my modern day betters would mostly discount this now. Along the same lines though, if you think about two major things, a) a Romano-British underclass as slaves and b) Other people, herdsman, like himself, largely occupying the hinterlands and uplands around more settled areas. Between the two, and moving along those areas, I reckon he would have received a friendly enough welcome of an evening. Perhaps, even incredulous, at his ambitions.

Interestingly, google calculates 5.9 days total travel. Obviously adding on extra for the time and a landscape without roads etc, even if one triples that, its still less than a month. As I suggest in the blog, he may have been fairly conscious of reaching an endpoint within just a few weeks – perhaps, both in terms of onward travel and , as you rightly say, managing a meagre enough individual food supply.

Thanks for the comment, much appreciated.

LikeLike